Key Facts and Summary

Originally published on School History

- At the start of the 20th century, Britain and Russia were vying for dominance over Iran. In 1908 the Shah (Emperor) of Iran signed an oil concession with a British company, giving it exclusive rights to search for oil in Iran and then sell it.

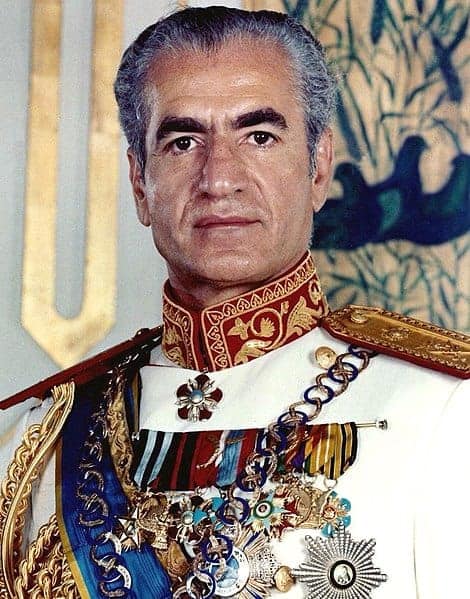

- In 1921, army general Reza Khan carried out a coup d’etat in Iran. He later took the title Reza Shah and became the first ruler of the Pahlavi dynasty.

- During Reza Shah’s reign, he introduced westernising reforms that were unpopular with some elements of the Iranian population, especially the powerful and influential clergy.

- Reza Shah was forced to abdicate his throne in 1941 by the British and Soviets, who invaded Iran to ensure that the oilfields did not fall into German hands during World War II. He was succeeded by his son, Mohammad Reza Shah.

- Elected as Prime Minister of Iran in 1951, Mohammad Mosaddegh planned to nationalise the oil industry so that foreign companies would stop taking the bulk of the profits out of the country.

- Mosaddegh resigned in 1953 following a coup orchestrated by the CIA and MI6 and supported by the Shah, whose powers Mosaddegh was trying to erode.

- Following the 1953 coup, the Shah’s rule grew increasingly authoritarian, while at the same time he forged closer ties to the U.S.

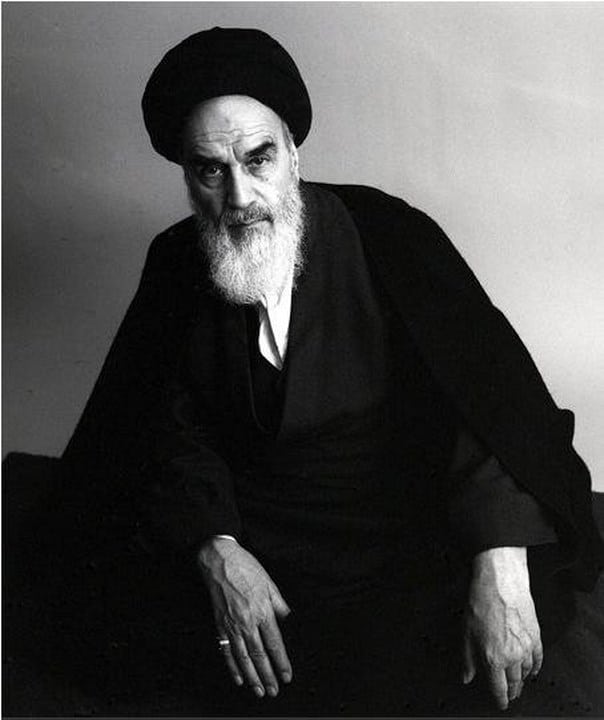

- In 1963 the Shah began a series of westernising reforms known as the White Revolution. Although he intended to strengthen support for his regime, the White Revolution caused widespread disaffection. The opposition was led by the cleric Ayatollah Khomeini.

- The oil boom of the 1970s caused more resentment towards the Shah, as his family grew fabulously wealthy but the oil profits failed to ‘trickle down’ to ordinary Iranians.

- On 7 January 1978, a newspaper based in the Iranian capital Tehran published an article critical of Khomeini. This sparked violent demonstrations in support of the Ayatollah.

- The following months saw a cycle of protests against the brutality used in the suppression of other protests. The Shah began to listen to and act on the demands of the opposition.

- A deadly terrorist attack on a cinema on 19 August 1978 prompted a new wave of protests as each side blamed the other for the atrocity.

- On 8 September 1978, the Shah declared martial law in Tehran and several other Iranian cities. Deadly clashes between the army and demonstrators led to the day being dubbed ‘Black Friday’.

- Over the period 9-13 September, oil and government workers went on strike in Iran. This was followed in October by a general strike bringing the country’s industry to a halt.

- On 5 November 1978, youths rampaged through Tehran burning businesses and buildings deemed as western.

- The Shah made a televised speech on 6 November 1978 in which he expressed sympathy for the protestors’ cause.

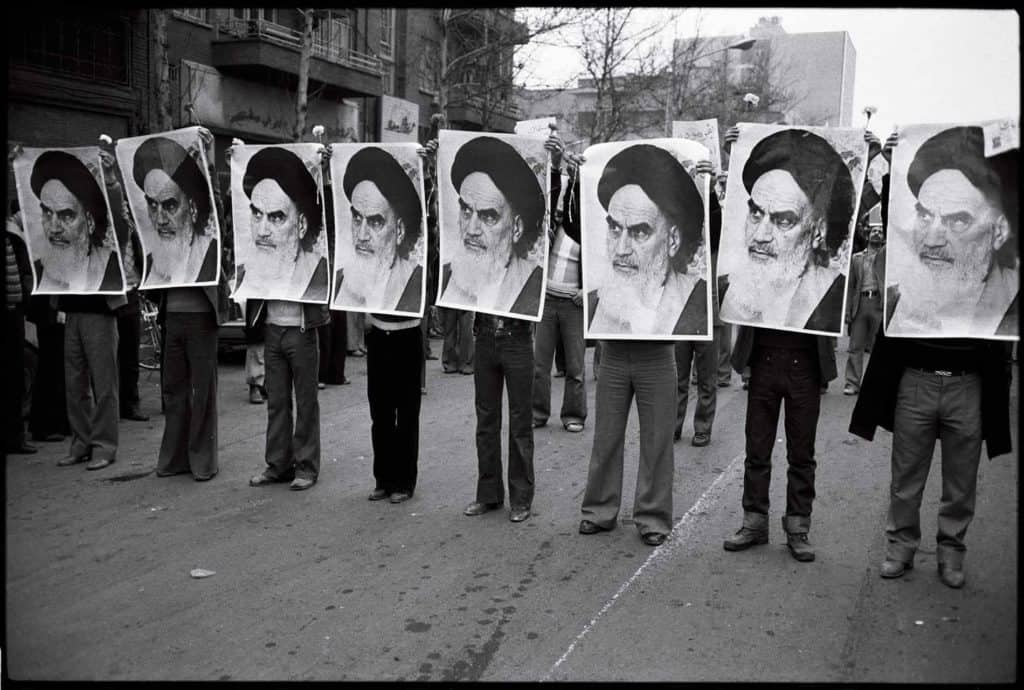

- During the Muslim month of Muharram, there were mass protests against the Shah, supported from exile in France by the Ayatollah Khomeini.

- By 16 January 1979, the Shah had lost support to such an extent that he and his family left the country for exile in Egypt.

- The Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran on 1 February to be welcomed by enthusiastic crowds. However, a struggle for power with Prime Minister Shahpour Bakhtiar led to further civil disturbances.

- On 11 February, the armed forces declared that they would not fight for Bakhtiar’s provisional government. This marked the true end of the monarchy and the start of Ayatollah Khomeini’s rule.

- Iran became an Islamic Republic in which the clergy had ultimate power over elected officials and the law.

Historical Context

Iran, formerly known as Persia, was never a colony of another country, but the colonial powers took a very close interest in it. During the 19th century, its location to the south of the Russian Empire had led to conflict with that country over the lands around the border. Britain also wanted to exert control over Iran’s leadership due to its proximity to India, the jewel in the crown of the British Empire. Britain feared that its rule in India could be undermined if Russia was able to control Iran. However, Iran became even more important to the industrialized world when a vast amount of oil was discovered there in 1908 by a British company. The company had negotiated exclusive rights to look for, extract, and sell Iranian oil with the Shah, the ruler of Iran. This oil would become vital to the British Empire and later to its war efforts, strengthening Iran’s ties with the west. The Shah’s willingness to share Iran’s natural resources with other nations, and the westernisation that this led to in Iranian society, was not welcomed by all sectors of the population. Many felt that Iran’s culture was being weakened and corrupted by its increasing ties with non-Muslim countries, a sentiment that was particularly strong among the powerful clergy.

In 1921, a military officer called Reza Khan overthrew the government in response to the weakness of the Shah and his signing of the Anglo-Persian Agreement, which many believed would make Iran (then still called Persia) a puppet state of Britain. By 1925 Khan had been given the title of Shah and became the first ruler of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Access to Iran’s oilfields became a pressing concern of the British in World War II. Now allied with Russia in the form of the USSR, Britain could not risk Iran falling under the control of its enemies. Reza Shah was rumoured to have German sympathies, and so he was forced to abdicate by the Allies. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, became the new Shah. In 1951 a new prime minister was elected, Mohammad Mosaddegh. He promised to nationalise Iran’s oil industry, taking it back from foreign control. He also wanted to reduce the powers of the Shah. Mosaddegh was supported by Iran’s communist party, although he was not a communist himself, and this was enough for the British secret service, MI6, to persuade the American C.I.A. that they needed to remove the prime minister from power. A coup was orchestrated with the backing of the Shah, and Mosaddegh was put under house arrest. From then on, the Shah’s rule grew more autocratic. Through the 1960s, he rushed through unpopular modernisation programmes in what was known as the ‘White Revolution’. The cleric known as the Ayatollah Khomeini spoke out against the Shah’s reforms and was forced into exile. The oil boom of the 1970s saw the Shah’s family become tremendously wealthy, but the economic benefits were not felt by many of the population.

The Revolution

During the 1970s, opposition to the Shah in Iran came from a variety of sources. Muslim clerics did not like his westernising and modernisation, intellectuals objected to his autocratic rule, and there were many rural workers who had been forced into the cities by his urban-focused reforms. The decade had seen an oil boom, but also high inflation. The government’s attempts to control inflation had caused living standards to plateau. Opponents of the Shah’s regime were often censored or even tortured. An alliance between the disparate groups of opponents was formed, with the aim of overthrowing the Shah. In exile, Ayatollah Khomeini preached against the Shah, becoming a figurehead for the opposition movement.

In January 1978, a Tehran-based newspaper, Ettela’at, published an article criticising Khomeini. A group of students in the city took to the streets to protest in support of the Ayatollah, and they were soon joined by larger-scale demonstrations against the Shah’s regime. The Shah himself, and the world at large, was shocked by the scale of the protests and the strength of feeling against him. He moved to suppress them, and his security forces were so brutal in dispersing the demonstrations that many protestors were injured and some were even killed. The deaths created martyrs for the revolutionary cause, and also had another knock-on effect. Shi’a Islam, the official religion of Iran, has a tradition of holding memorials for the dead 40 days after their passing. So 40 days after the first protests, memorials were held for the slain protestors, sparking more protests and more deadly repression. Then 40 days after this, there were more memorials, and more protests and the cycle continued into the summer of 1978.

On 19 August 1978, terrorists set fire to a cinema, killing hundreds of people. The true motives behind the attack have never been uncovered: the Shah’s supporters blamed Islamic Marxists, while revolutionaries claimed the Iranian secret service had carried out the attack on the Shah’s orders. The attack on the cinema was one of the key triggers for the revolution, as the protests that followed it escalated and led to the Shah’s downfall.

The Shah imposed martial law in Tehran on 8 September 1978. After the army opened fire on thousands of demonstrators, dozens were killed. The day came to be known as Black Friday. The following week saw workers go on strike at oil refineries and government offices. When this mushroomed into a general strike at the end of October, Iranian industry was paralysed. On 5 November there was rioting in Tehran, targeting buildings and businesses that were perceived as westernised. The Shah tried to placate the protestors, dismissing many representatives of his government who had been accused of corruption. He also agreed to give striking workers pay rises.

Despite the conciliatory measures from the Shah, the protests continued. In the Muslim month of Muharram, starting that year on 2 December, millions of people marched calling for the end of the Shah’s rule and the return of Ayatollah Khomeini. Khomeini was at that time in France, where he was using the western media to publicise the anti-Shah cause. Although his intention was to turn Iran into a theocracy, a country governed by religious law, Khomeini allowed the west to think that he only wanted democracy.

The Shah decided that it was time for him to leave Iran. On 16 January 1979, he appointed a new prime minister, Shahpour Bakhtiar, whom he hoped would be able to rein in the Ayatollah and stop him imposing a theocracy. He then took his family and left for Egypt. Huge crowds again took to the streets, this time in celebration at the Shah’s departure. Prime Minister Bakhtiar invited Ayatollah Khomeini to return to Iran, which he did on 1 February 1979. The leader of the revolution was greeted rapturously. However, he immediately denounced Bakhtiar’s government and nominated his own replacement prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan. With Bakhtiar and Khomeini at a standoff, support for Bakhtiar melted away. By 11 February, the armed forces had declared that they would remain neutral and not fight for him. This marked the end of Bakhtiar’s government and the official end to the monarchy in Iran.

On 1 April 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini, now in effective charge of Iran, named the country an Islamic Republic. The clergy moved to distance themselves from the left-wing intellectuals who had been their allies in the revolution, and Iran returned to being a conservative Muslim nation after decades of westernisation. Women’s rights were rolled back and strict dress codes were enforced. Islamic law was enforced by the Ayatollah’s newly created Revolutionary Guard, whose brutality often surpassed that seen under the Shah. By the end of the year, a new constitution enshrined religion as being dominant in the state and gave the leading cleric, at that time Khomeini himself, extensive powers.

Chronology

Iran, formerly Persia, was ruled by a Shah, or Emperor. When oil was discovered in the country in 1908, a British company negotiated exclusive rights to mine for oil in Iran. This led to increased westernisation and close ties with non-Islamic nations, which were unpopular in many sections of Iranian society, particularly the clergy. In the 1960s, Mohammad Reza Shah embarked on a rapid programme of reforms that made Iran more modern, industrial and urban. Criticism of these dramatic changes was led by the cleric Ayatollah Khomeini, who was exiled for his opposition to the Shah. By the 1970s, the Islamic critics of the Shah had united their voices with the intellectual left, who disagreed with the authoritarianism of the regime. A newspaper article criticising the Ayatollah Khomeini in January 1978 led to a series of protests that were suppressed by the authorities with deadly force. After a year of civil unrest, encouraged by the Ayatollah Khomeini from exile, the Shah was forced to leave Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini returned to the country in February 1979 and within two months had declared it to be an Islamic Republic, governed by religious laws, with himself as the leading cleric.

References:

[1.] Roberts, J.M., The Penguin History of the World (Penguin, 1992)

[2.] https://www.britannica.com/event/Iranian-Revolution

[3.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iranian_Revolution

Image source:

[2.] https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/16/Roollah-khomeini.jpg